This is the seventh installment of my newsletter about theater, process and practice. If you’re new: Welcome! You can find previous installments here: We All Need a Prehistory, A Heap Of Broken Images, The Art of Transitions, Taroturgy, Datamoshing, and Not light, not darkness, but something in between.

In 1957, something strange happened in the world of theater.

Samuel Beckett, already famous for Waiting for Godot, wrote a play called Act Without Words.

The action takes place in a desert and the cast consists of just one man who moves, gestures, interacts with objects—but never speaks. As the title announces, this play has not a single spoken line of text.

Critics didn’t know what to make of it. Neither did audiences.

Over the next few decades, a tiny cohort of playwrights—Peter Handke in Austria, Ota Shogo in Japan, Franz Xaver Kroetz in Germany—began writing plays that eliminated the very thing theater had relied on for 2,500 years: words.

There’s something deliciously paradoxical about theater that refuses to speak.

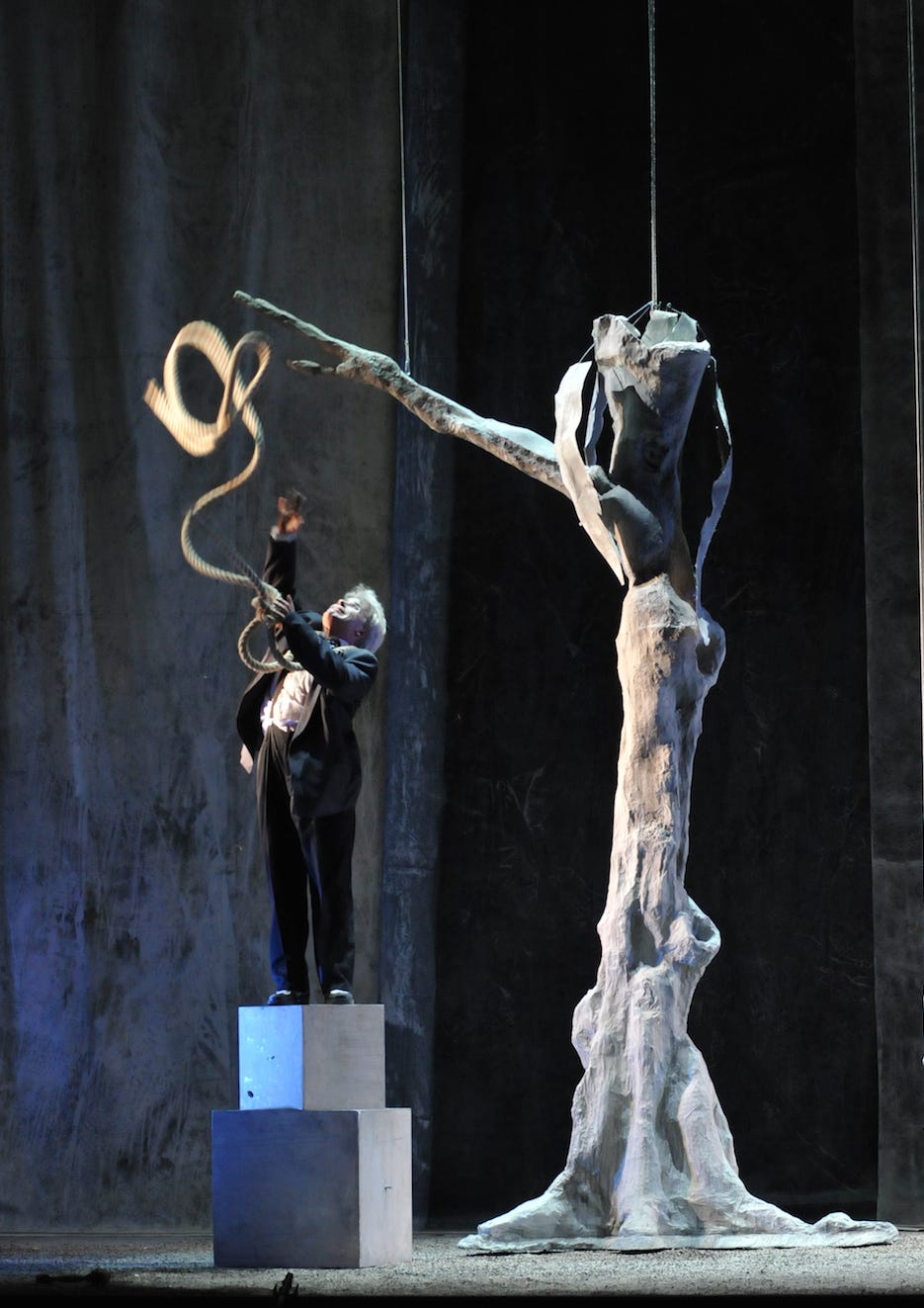

This fall, I’m directing My Foot My Tutor, a play without words by Peter Handke. This is my second foray into this odd niche in the dramatic canon and I find myself wondering: what are these plays trying to do? What impact do they have on an audience? In their muteness, what can they express about the world and about theater itself?

To my knowledge there are only eight of these plays in existence.1

[My theater nerd friends who read this: do you know of any other plays that fit this category? See the footnote for the titles I’ve identified. If you know of any others please let me know!]

Together, these eight plays represent perhaps 0.001% of all theatrical works ever written. And yet, I would argue, they may be some of the most significant plays of the modern era.

Why? Because they address a central problem of the human condition and, in the process, infuse theater with new vitality.

The Fish Don’t Know They’re Wet

We live inside language the way fish live in water: mostly unaware of the medium that surrounds us.

Words seem so natural, so transparent, that we forget they’re one of the most sophisticated technologies we have invented. We speak and things happen. You say “Come here,” “I love you,” “Pasta or pizza?” and your words unleash changes in my neurochemistry that result in images, and feelings and behavior.

It’s like magic.

Words have allowed us to build civilizations, transmit knowledge, and enable cooperation on a scale no other species has achieved. Their power is so strong that it’s no surprise Western theology has imagined God to be a word, Logos, divine language.2

Yet, all technologies come with unintended consequences. It’s not just that language allows us to lie, manipulate, and deceive. The problem goes deeper.

Take this simple test: Close your eyes and focus on your left hand. What do you actually experience? If you’re paying close attention, it’s not really a hand at all—it’s a collection of sensations, pressures, temperatures, tinglings. But the moment you think the word “hand,” something happens. Those raw sensations get replaced by a concept, a representation, a mental file labeled “hand” that you’ve been building since childhood.

The word doesn’t describe your experience—it replaces it.

And the scale of the replacement is staggering. What does the word “hand” actually mean? You might say it’s the part of your body at the end of your arm, with five fingers. But notice what just happened: you defined “hand” using other words—body, arm, fingers—that themselves need defining. What’s a body? A physical form. What’s physical? Having material substance. What’s substance? Matter that occupies space. What’s matter? Not energy. What’s energy? Not matter.

We’re caught in a linguistic house of mirrors. Every word points to other words, which point to still other words, in an endless hall of reflections that never quite reaches the thing itself.

It’s enough to make you dizzy.

Another problem is that words are never neutral. Every word carries invisible baggage, smuggled in by whoever had the power to define it first.

Compare the phrases “illegal immigrant” and “undocumented worker.” Same person, but completely different emotional, and ideological freight; and neither phrase allows us to encounter the actual human, the irreducible living presence that exceeds linguistic categories.

Or take something as innocent as “sunset.” We say it every day without thinking. But embedded in this simple word is a millennia-old mistake. The sun isn’t setting—we’re rotating away from it. “Sunset” preserves a worldview where Earth sits still at the center of everything. Every time we say it, we sound like Ptolemy, not Copernicus.

As it turns out, we don’t really speak language—it speaks us.

The Quiet Revolt

“More and more my own language appears to me like a veil that must be torn apart in order to get at the things (or the Nothingness) behind it. Grammar and style. To me they have become as irrelevant as a Victorian bathing suit […] As we cannot eliminate language all at once, we should at least leave nothing undone that might contribute to its falling into disrepute. To bore one hole after another in it, until what lurks behind it —be it something or nothing— begins to seep through; I cannot imagine a higher goal for a writer today.”

Samuel Beckett

“What bothers me is people’s alienation from their own speech […] It isn’t their language anymore, so they can’t even communicate. When people are alienated from their language and their speech, as workers are from their products, they are alienated from the world as well.”

Peter Handke

Given our linguistic alienation, it becomes clear why playwrights like Beckett and Handke arrived at a radical solution: the most profound way to use language might be to throw it away entirely.

This is why these handful of plays without words matter.

They form a secret stream within modern theater, a kind of backdoor to help us escape the prison of language. With their silence, they dynamite our verbal hall of mirrors. With their simplicity, they show us existence before words kidnap it from us.

Of course there’s a sharp irony here. These wordless plays aren’t really wordless at all.

Open the script of My Foot My Tutor and you’ll find pages and pages of text—elaborate, detailed instructions for every gesture, every movement, every costume piece the characters wear.

This, it turns out, is a play made by putting the humble stage direction on steroids.

The paradox is that to eliminate language from the performance, these playwrights had to use more language than ever before. At least that’s how these playwrights chose to notate their intentions so that actors and directors in other places and times can perform these works.

I imagine one could draw diagrams, create storyboards, eliminate text altogether. But pictures are symbols too. And a symbol is just another form of language. Even if you tried to escape words by using images, you’d still be trapped in the same symbolic prison, just with different bars.

Yet, as I tell my students, the script is not the play.

A script is like sheet music—it’s not the song itself, just instructions for creating it.

These writers understand the difference between the map and the territory, and when actors perform these wordless pieces in front of you, something extraordinary happens.

Without the filter of speech they must inhabit their bodies completely.

And you, the audience, deprived of verbal explanation, must pay attention in an entirely different way.

The quality of that attention will be the subject of a future installment where I’ll continue exploring the power of these plays.

Samuel Beckett’s Act Without Words I and Act Without Words II.

Ota Shogo’s “Station” plays, including The Water Station, The Earth Station, and The Wind Station.

Peter Handke’s My Foot My Tutor and The Hour We Knew Nothing of Each Other.

Franz Xaver Kroetz’s Request Concert.

“In the beginning was the Word, and the Word was with God, and the Word was God.” John. 1:1