Taroturgy

(Or What The Ace of Cups Asked Me)

This is the fourth installment of my newsletter about theater, process and practice. If you’re new: Welcome! You can find previous installments here: We All Need a Prehistory, A Heap Of Broken Images, and The Art of Transitions.

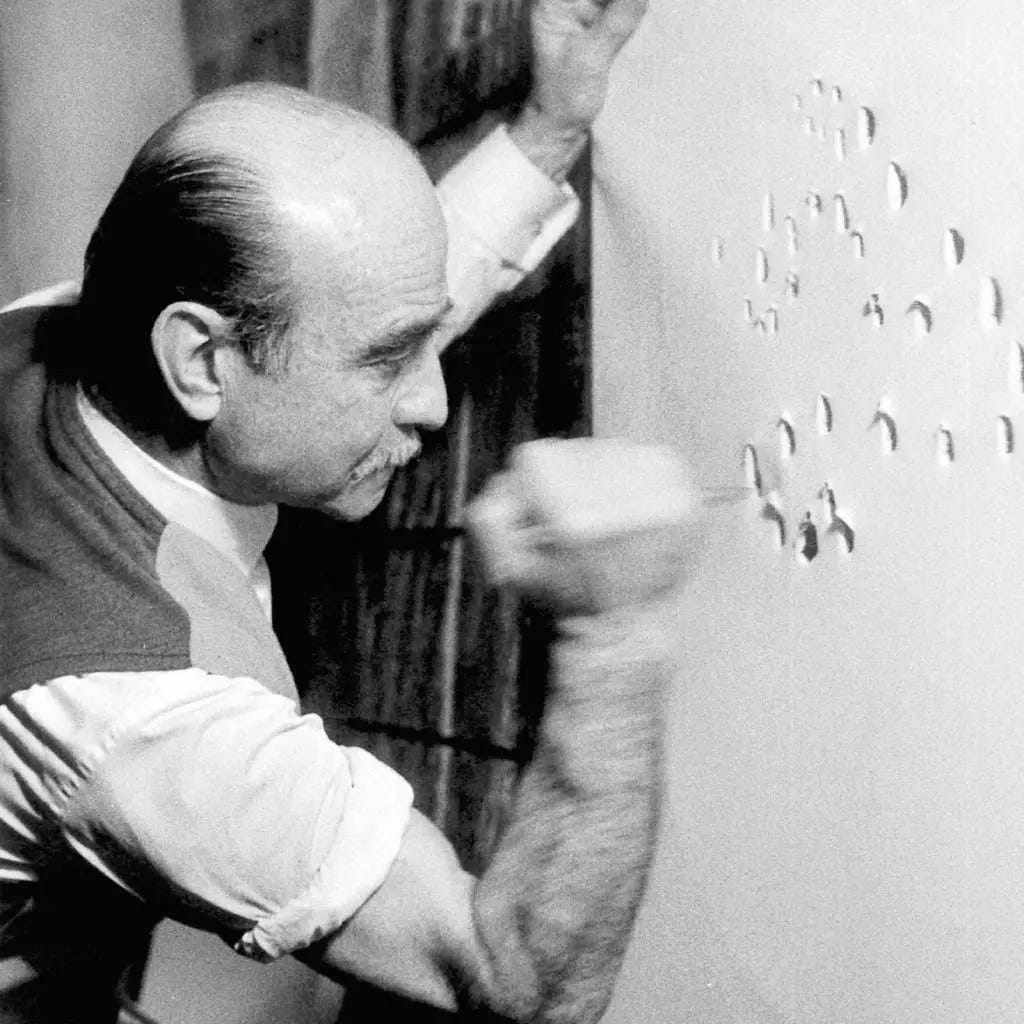

Creative entropy? Argentinean artist Lucio Fontana working on one of his Cut Painting by stabbing the canvas

Dramaturgs are the Swiss Army knives of the theater world—experts in history, criticism, research, and structure who act as thought-partners for playwrights and directors.

Traditional theater institutions often value dramaturgs for their ability to impose order on creative chaos, for “making something palatable and normative and recognizable”1 to season ticket holders.

But what if a dramaturg does the opposite? What if their greatest gift is to destabilize your process, injecting creative entropy into ingrained assembly-line thinking?

Recently, I had a fascinating dramaturgy sesh with my friend the artist Ajani Brannum for my latest endeavor, The School of Memory. Ajani’s approach is unique: they utilize the Tarot deck to structure the discussion and question the material.

The element of chance inherent in the Tarot cards immediately interested me. It reminded me of composer John Cage’s use of coin flips in his work, or Brian Eno’s Oblique Strategies cards – both methods of infusing randomness and disrupting habitual creative patterns.

As far as process go, this session was a gem. If Ajani were a knife, they would be less Swiss Army multi-functionality and more piercing blade à la Lucio Fontana. Their sharpness cut through many mental ropes that were limiting my own vision of the project.

Capturing the full richness of our hour-long exchange would be impossible. Instead I’ve selected three post-facto reflections prompted by the cards and Ajani’s questions, and I’ll use them to tell you more about where I’m at with the project, including some unsettling discoveries I’ve made about my family history in the last month.

(If you’re new to the newsletter I recommend checking out my previous post where I talk about what I’m working on, so that what follows makes sense.)

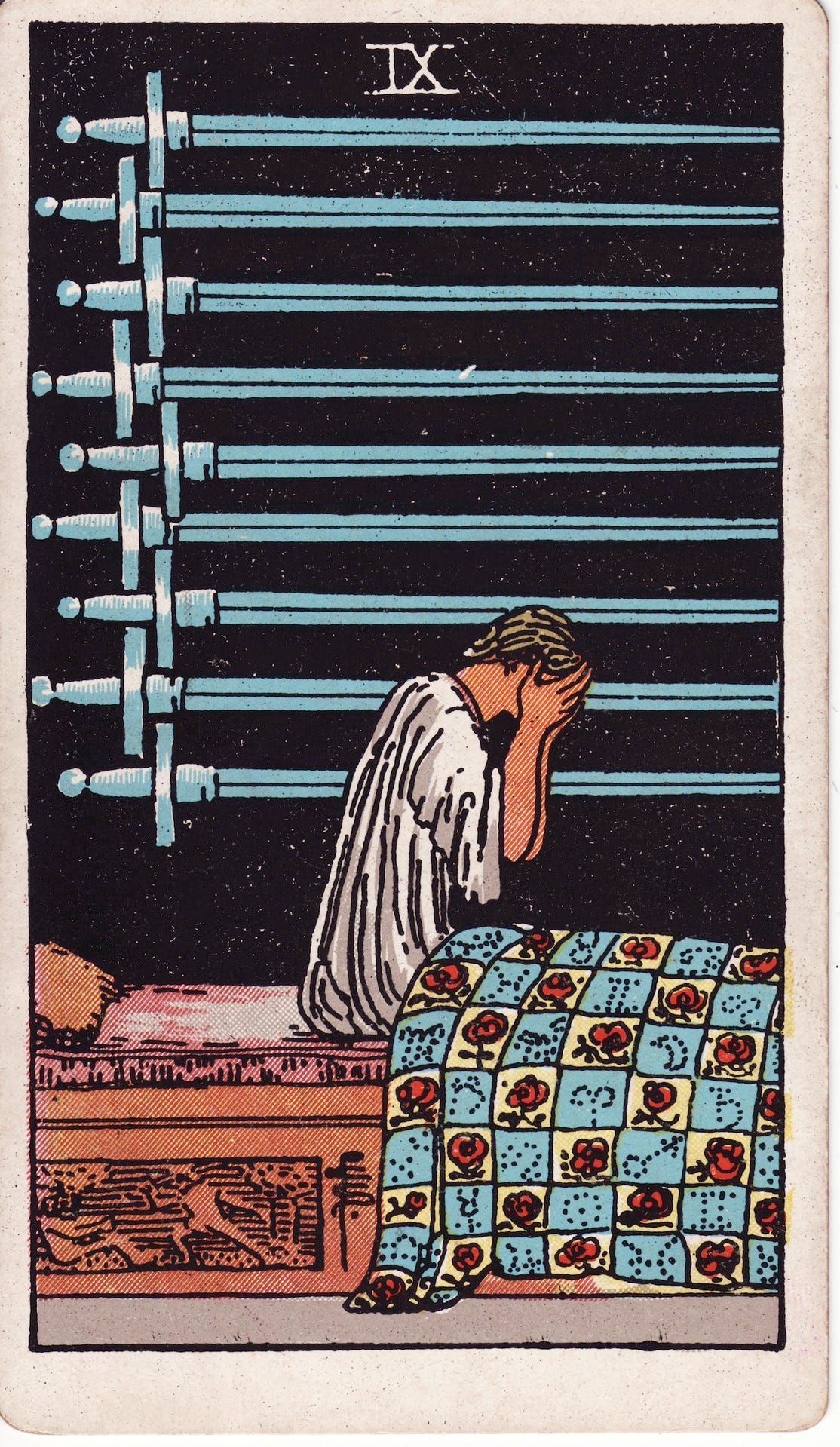

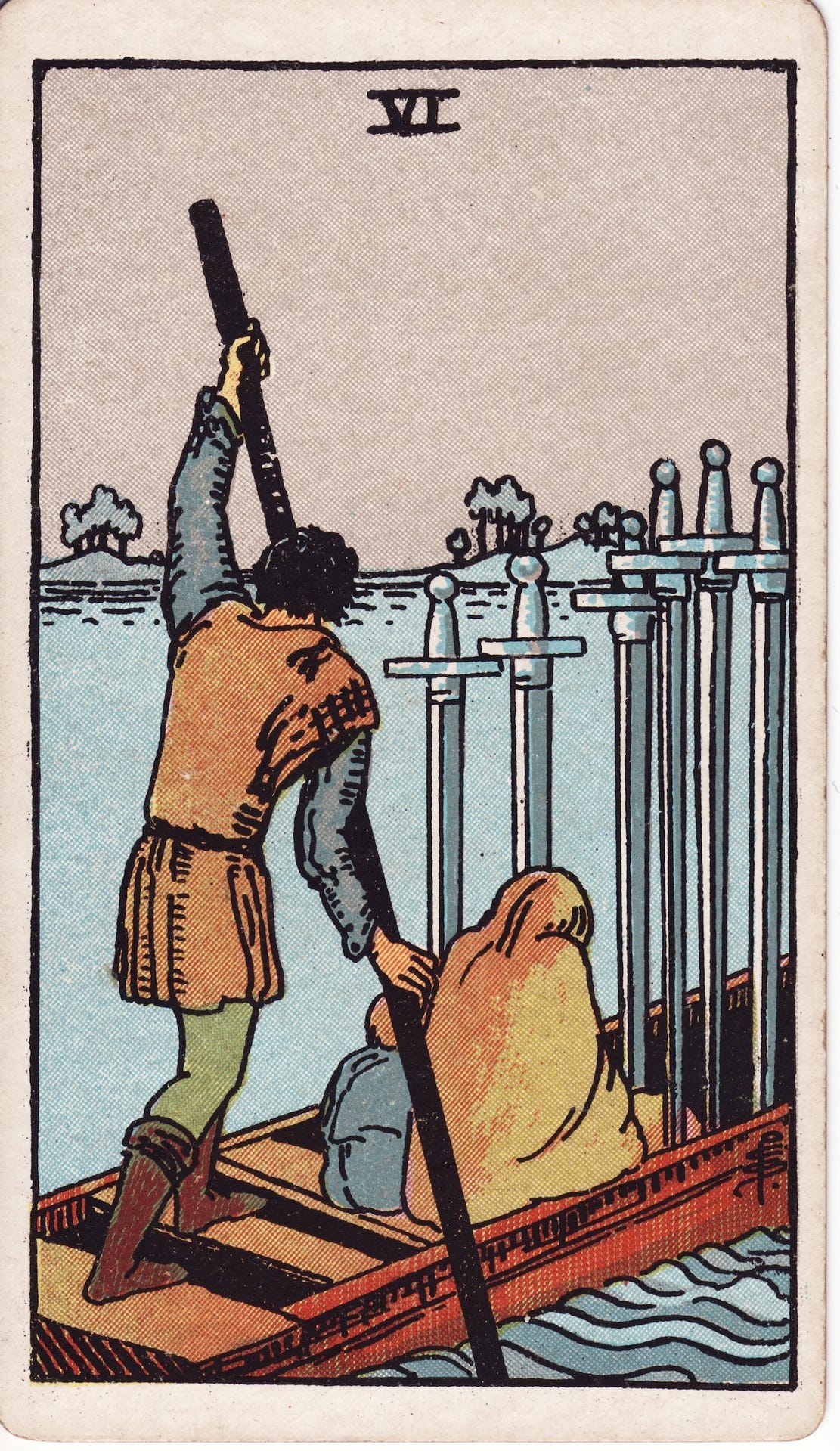

What’s one thing that you’re terrified to do or confront in performance?

Performing in front of my parents. Mom and Dad in the audience. Parental eyeballs like those swords in the card stabbing me with self-consciousness.

Once, at 17, I performed a Mario Benedetti story at an open mic. (Subject: NSFW. Tone: Lurid). Despite trying to keep my parents away, the moment I entered the stage I saw my father in the third row, beaming like I’m the next Brando, and zap! —all spontaneity and life evaporated.

Parental dread might be a symptom of a deeper affliction: oikophobia. Terror of origins. Fear of one’s roots. And with this project, I sense the fear has ballooned into a Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade float. It’s as if I’ll be performing not just for my dear progenitors, but for a spectral audience of predecessors who most certainly disapprove (look at their heads in black and white shaking with distaste and going: tst-tst-tsssttt).

But maybe that’s the point? Maybe I’m supposed to tell these ghosts something?

I think of W. H. Auden’s definition of art as “our chief means of breaking bread with the dead.”

Maybe this is not a play… but a banquet.

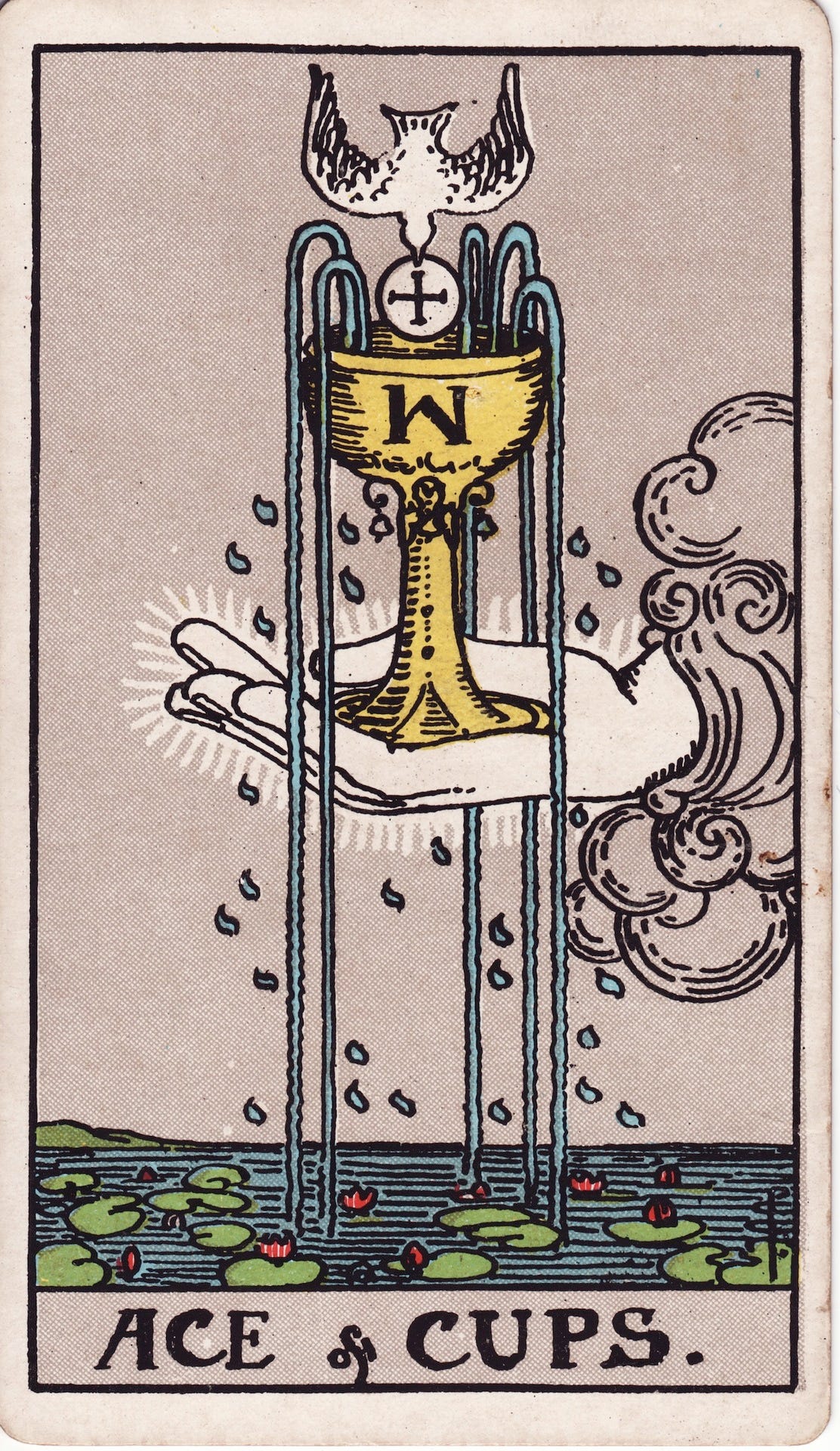

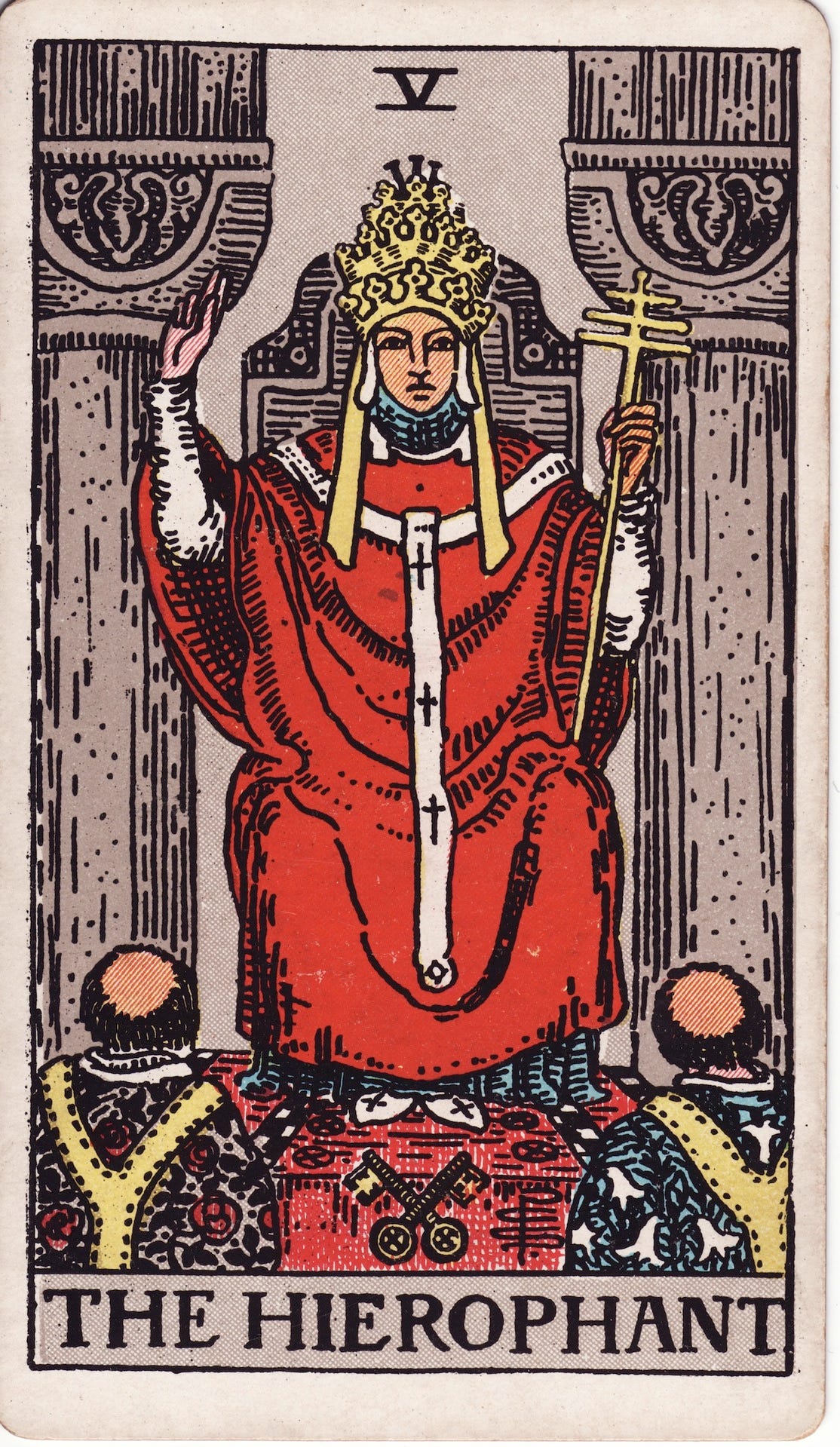

How is this work pursuing revelation?

Revelation: A surprising and previously unknown fact, especially one that is made known in a dramatic way. —New Oxford Dictionary

For years, this question gnawed at me: Why did the Fascists kill my great-grandfather at the war’s end?

Not having an answer gave the question its power.

The story my cousin told me, the ‘family secret,’ seemed to be hiding something, but what?

I spent June immersed in digital archives, scouring databases of war victims, requesting military files from the Spanish government, playing detective.

This surprised me: I got very emotional when I unearthed my great-grandfather’s name:

Jesús Calleja Doñoro

I found out he was executed on June 12, 1939. He was 45 years old.

With this information came the first discrepancy: my great-grandfather was not murdered in his village as I had always believed. Instead, he was arrested and taken to Alcalá de Henares (my hometown, a mere 16 kilometers away), where he faced a firing squad at dawn alongside 10 other men. Their bodies were very likely buried in a mass grave in the old cemetery in Alcalá.

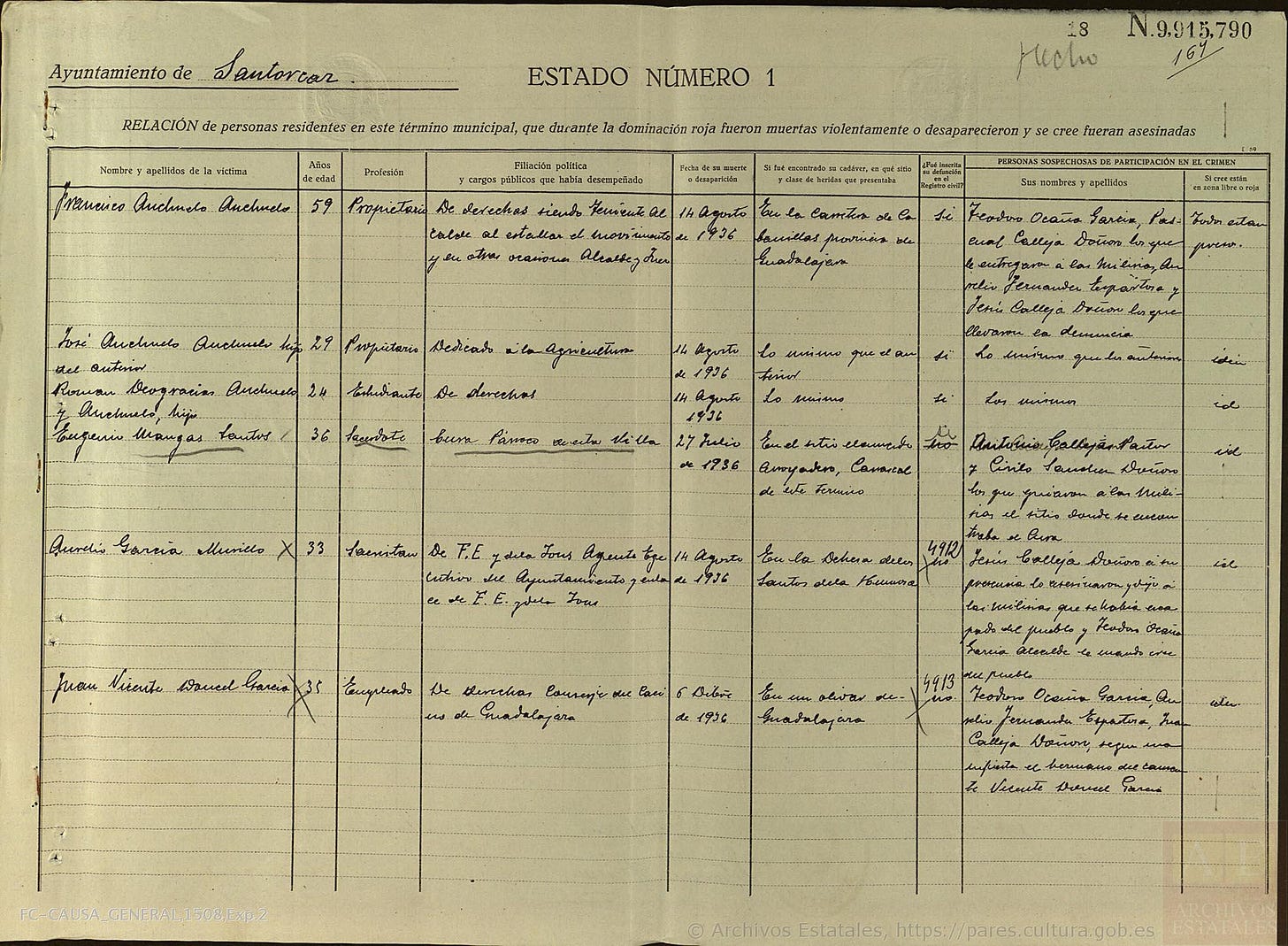

Then, a bombshell: a photograph of a military ledger hinting at the reason behind his death. My sister and I spent an hour on Zoom, deciphering together the spidery handwriting.

Here’s what we believe it reveals:

In 1936, at the beginning of the war, left wing militias loyal to the Republic stormed our village. They set the statue of Christ, the Virgin and the saints in the church on fire. They arrested a 59-year-old landowner, labeled a “right-winger,” his two sons (24 and 29), the village priest (36) and the sexton (33). Days later, their bodies were discovered in a ditch.

It appears my great-grandfather was complicit in these murders.

It’s hard to reconstruct what happened exactly, but according to this document he pointed the finger, he identified those to be targeted, condemning them to their fate.

Three years later, the Republic lost the war and the Fascists came knocking for retribution.

Talk about revelation.

The cup overflows with new questions.

What’s an alternative paradigm to memory? How do you go beyond the binary remember/forget?

I had never thought—not once—about my great-grandfather until my cousin told me he was killed. For me, right up until that moment, this man did not exist. But when I heard the ‘family secret,’ he suddenly became possible: this man was born for me right at the moment of his death.

For years, the comfort of having an ancestor killed by the Fascists was perversely satisfying. After all, victims are the heroes of our time.

Now the plot has thickened, the complexity metastasized.

I’m compelled to ask: why did my great-grandfather participate in those murders? What’s the story behind this story? Was it political conviction, personal vendetta, class warfare, or simply the brutal logic of war? How does this knowledge change me? How much of what I feel is sadness, how much shame, how much admiration, how much confusion? Is this a story I would want to pass on to my niece, would I want to burden her with this knowledge when she grows up?

Each inquiry deepens the mystery. The archives offer no real answers, only more questions.

As my session with Ajani concludes, a new possibility emerges: perhaps this project is less about unearthing facts and more about crafting fictions for myself that transcend them.

“Imagine yourself alongside your great-grandfather,” Ajani suggests. “What conversations could heal this story? What dialogues could nourish you?”

My unconscious takes up Ajani’s suggestion, but gives it a perverse twist. On my last night in New York I have this dream:

A frantic knock at the door.

I open it and a stranger rushes in, begging me to hide him.

He crawls under the bed, looks out and, then—I recognize him: it’s my great-grandfather.

And I realize that he has come to kill me.

On his first day at American Repertory Theater, then dramaturg Gideon Lester received this instruction from director Robert Woodruff:

“Your job is to keep me brave.”2

I felt Ajani fulfilling that role during our session, holding my imagination to a higher standard of courage. A courage to match the complexity of recent revelation; a courage to envision this work’s import beyond its 90-minute stage life; a courage to forge a personal myth from memory, historical trauma, the unknown, and the forgotten; a myth woven from the psychic material of dreams and personal prophecy, yoking the entire endeavor to that unfolding chain of being that’s both familial and cosmic.

The conversation left me with more questions than certainty.

And yet, it felt as though we had pierced through a canvas wall together, emerging not into another room, but onto an entirely new landscape.

For this, I’m deeply grateful.

Working on a project that could use some disruption? If you’re interested in booking a dramaturgy session with Ajani, you can contact them here. I highly recommend it.

Gideon Lester interviewed by Nature Theater of Oklahoma in OK Radio, Episode 37, January 10, 2013

Ibid.

Glued to these updates. What a story you are unearthing. Grateful to be along for the ride.

We love to see it! I appreciate the share - can't wait to see what the work brings you as it unfolds. Here's to more dramaturgical stabbing/slashing 🔪🤍