We all need a prehistory

On fake beginnings and how to direct plays you don’t love

Hi, hello, welcome! I’m starting a newsletter about theater, process and practice that I think you might enjoy. Feel free to say hi or leave a comment, and thanks for reading!

Dionysos is god / of the beginning / before the beginning.1

That’s how Anne Carson begins her translation of Bakkhai, a Greek tragedy about the god of theater, wine, madness and dismemberment. She continues:

What makes / beginnings special? / Think of / your first sip of wine / from a really good bottle. / Opening page / of a crime novel. / Start / of an idea.

I’m beginning the year with a brood of beginnings. This newsletter, for instance—which I decided to start to be in conversation with you, fellow artists, family and friends, as a way to share and discuss and document process (funny how, inevitably, sooner or later, in conversations with other directors this topic always comes up: we’re so interested in, so intrigued by each other’s processes, by how other creatives approach this thing which is the making of an artwork, and the making of a life built around an artistic practice).

Beginnings have their own / energy / ethics, / tonality, / color. / Greenish-bluish-purple / dewy and cool / almost transparent, / as a ripe grape. / Tone of alterity, / things just about to change, / already looking different. / Energy headlong / and heedless / and shot / like a beam. / Ethics / fantastically selfish.

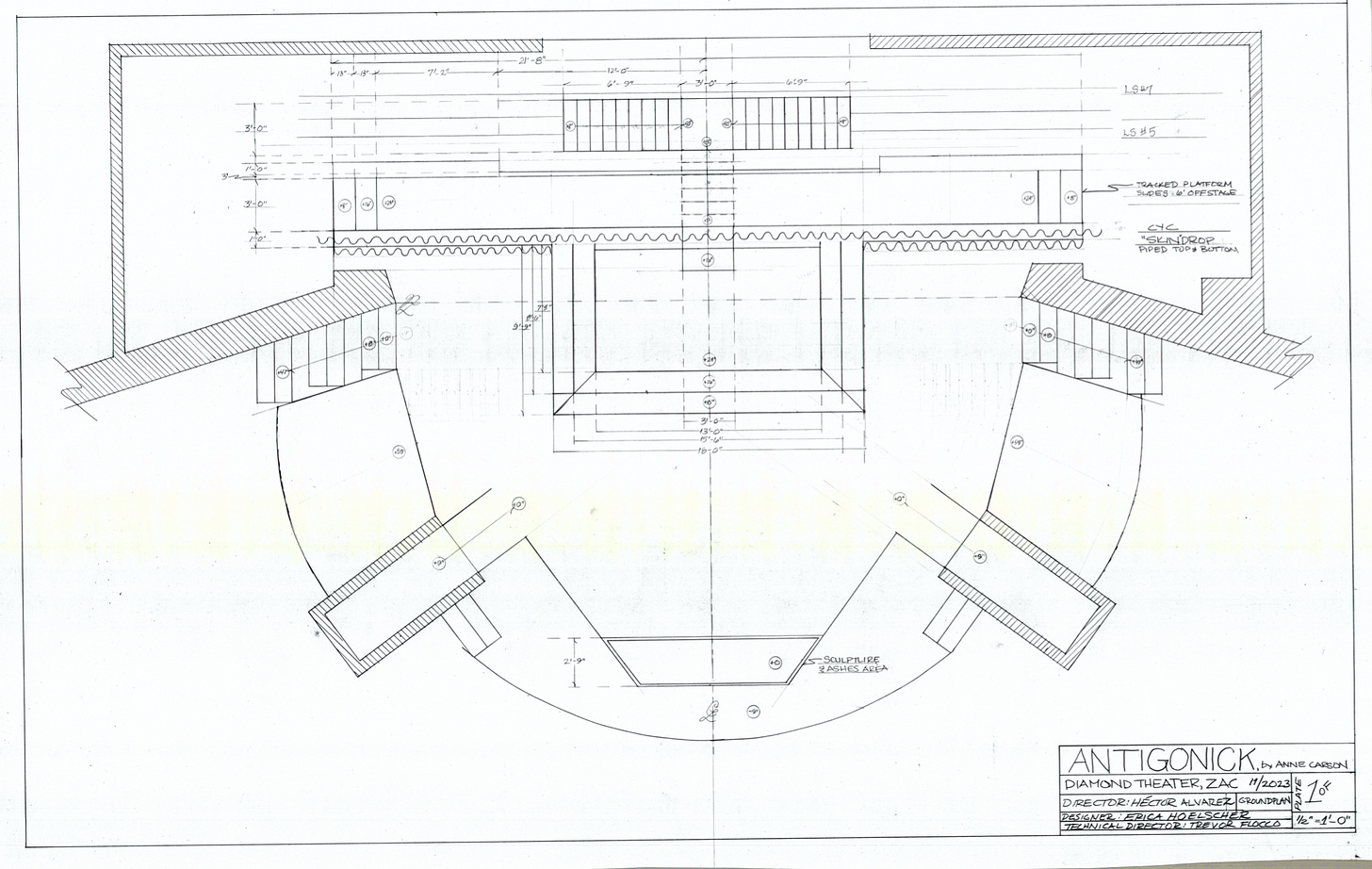

Last week I started rehearsals for a production of Antigonick at Lehigh University, where I’m the Theodore U. Horger Artist-in-Residence in the Performing Arts (another beginning). Antigonick is one of Anne Carson’s remarkable translation-adaptations of a Greek classic, in this case a condensation of Sophocles’s tragedy about a girl who breaks the law in order to bury her dead brother.

I must confess: I do not love Antigone. Of all the major tragedies this is the one that least resonates with me, the one that doesn’t fill me with ‘energy headlong and heedless.’ Is it because I find her, the character, baffling? Antigone is fervent, obsessive, monomaniacal: the only other characters in literature that I think come close to her are Electra and, in a distant third place, Ahab from Moby Dick. Also, Antigone only appears in three scenes, then dies in the middle of the play: she makes her point and exits forever, leaving a smoking crater that I don’t know how to inhabit.

Predating Christ by a few centuries Antigone says: “I was born for love, not for hate.”

Antigone, I do not love you. I find you ‘fantastically selfish’ and strident. Frightening. I did not choose to direct you but was given you as a task, as a burden. I do not love you because I do not understand you, Antigone, and because I fear I will not do you justice in a play that’s so concerned with the idea of what is just.

Usually, I do not think that love is a prerequisite for good work. Ambivalence, animosity: these can be more productive energies for a director wrestling with a text. But in this case love is central to the dramaturgy. One of the most beautiful moments not just in the play but in the entire Western canon is the choral Ode to Love, the one that begins:

Eros, no one can fight you / Eros, you clamp down on every living thing, / On girl’s cheeks, on oceans, on wild fields…

Why does this beauty fail to move me? Why does it trouble me? Is it because I had to translate this text from the Ancient Greek in high school (excruciating and tedious work) and then made the stupid choice of reading it to the girl I had a crush on just as her boyfriend entered the classroom? Or is it because the love coursing through Antigone is not just any kind of love either, but a love so extreme, so incestuous (dare I say monstrous?) that she shouts she wants to lie in the grave with her brother ‘thigh to thigh’?

Antigone: you force me to recognize my smallness, my conventionality; you force me to see that my secret prayer has been for many years: ‘may I never be cursed with a love so big and destructive.’

Lecturing in Japan / Stephen Hawking was asked / not to mention that the universe / had a beginning / (and so likely and end) / because it would affect / the stockmarket.

Let’s be practical Héctor: the question to ask is not ‘How do you direct a play you don’t love?’ The question to ask, now, is: ‘How do you find an opening, a pinhole, a pore through which to infiltrate the work?”

There’s always something there before we start.

I remember opening the first page of Carson’s script on an airplane from LA to the Lehigh Valley, to the job interview for this position I now have. And remembering that moment I discover my pinhole.

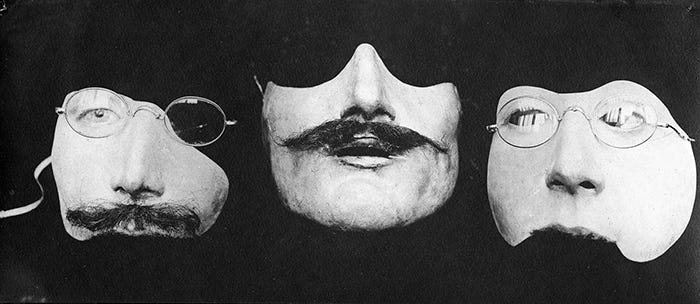

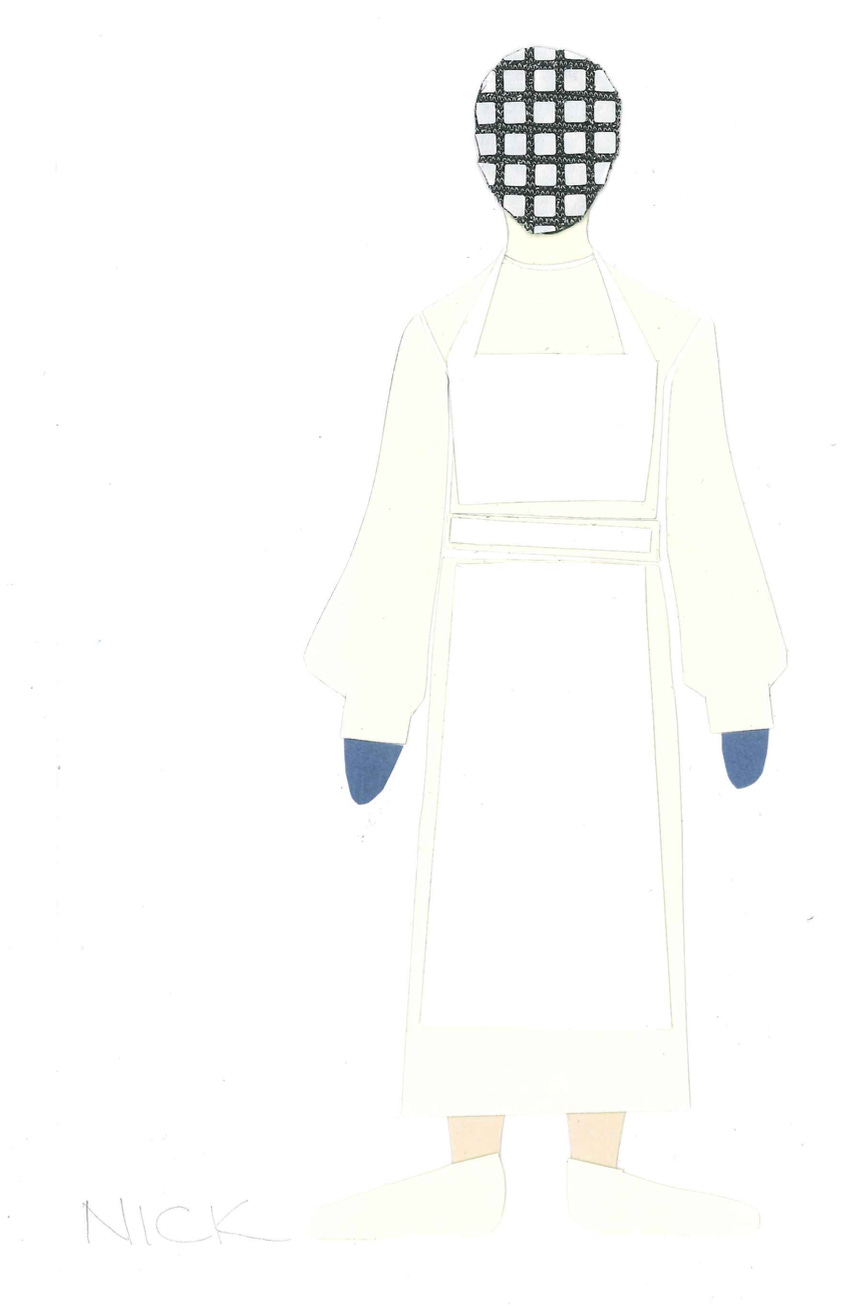

One of Carson’s innovations consists in introducing a character called Nick, a character who does not exist in Sophocles’s original and of whom she offers the most cryptic of explanations:

She says only one more thing about this Nick without name or history, about this Other who measures. The play’s last line:

So at the beginning, for me, the obvious (but hard) question:

Measures what?

Not the question ‘Who are they?’ but the question ‘What is it they are doing?,’ both onstage, in a very practical sense, and also in a larger poetic sense (as in: what are they doing in and for this play? How are they functioning?)

I play with this question and the playing cuts through the skin of the text, it nicks this baffling play I don’t love and draws just enough blood, makes enough of a gash, enough of a portal through which I can enter Antigone’s world.

Speculation aside, / we all need a prehistory. / According to Freud, / we do nothing but repeat it. / Beginnings are special / because most of them are fake. / The new person you become / with that first sip of wine / was already there.

I’ll tell you more about what Nick measures in our production in the next installment of the newsletter. For now, I end with a couple more thoughts on beginnings:

The end is always already there and beginnings arise out of cessation. In preparation for our first day of rehearsal, I ask actors to bring in a photograph and items of someone they have lost in order to build an altar. Like Antigone, I want us to honor the dead. One actor builds a shrine with candles to all her family members who died in the Holocaust. Another brings a little Christmas tree and a teddy bear to remember his sister who was stillborn one Christmas Eve fourteen years ago. I too build and altar for my grandmother, who just passed away in November.

In the churn of the first rehearsal, we make sure to sit down in stillness before our altars, and we talk to the dead.

Here I find not Antigone’s love, but mine.

Another beginning: I’m 16 years old and I play the role of Haemon (Antigone’s fiancé) in a high school production in Hong Kong, the first time in my life I perform in a foreign language. My English is pretty much non-existent, so I learn my lines phonetically against a Spanish translation, hoping the thick-accented sounds coming out of my mouth can carry some shred of the text’s meaning. I’m young and clueless. I have long hair and earnestly held ideals. I’ve rebelled against family, country and upbringing by leaving behind everything I know, and it feels like something that very much resembles an independent, adult life is precociously beginning. I love this life and love the theater, I love it almost more than anything else.

This now feels like ancient history.

As I go into rehearsals now, I need to sip the wine of memory until I forget everything I think I know about Antigone. I must drink until I remember this forgotten me which has been there all along.

Dionysos is pleased / if he can cause you to perform, / despite your plan, / despite your politics, / despite your neuroses, / something quite previous, /

the desire / before the desire, / the lick of beginning to know you don’t know.

All verse sections in italics come from the ‘Translator’s Note on Euripides’ Bakkhai’ by Anne Carson, London: Oberon Books, 2015.